Internexit?

The UK’s storming off (again), blue-checkmate Elon, the dangerous rise of internet points, and more

Service update: It’s an expanded issue this week, partly as an apology for last week’s no-show (we are now properly up and running) and partly because there is just so much going on in the world of tech. Welcome also to our new Sunday afternoon/evening timeslot – hopefully giving you something to think about as we get set for the week ahead

Also: if you’re reading this and liking it – please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. A few of you have already done so (especial thanks to those who’ve paid for a year in advance), but not enough yet to make it viable. If you’re still on the fence, there’s a few more weeks of free posts to come – and do let me know if there’s something we could add or change to help make your mind up.

Online safety, and the bill that comes with it

The UK has been trying for about four years to pass wide-ranging legislation to fix the internet – or at least make it less harmful. The legislation has outlasted three prime ministers, many more secretaries of state, and two iterations of the department that approved it.

It’s been renamed and redrafted, and expanded into almost total incomprehensibility – and yet inevitably still has wide cross-party support, largely because no-one wants to vote against something with “online safety” in its title, especially when the Home Office has cleverly (if covertly) positioned being against the bill as being against the protection of children. Some of the campaigns were anything but subtle.

This is something of a shame as anyone who has looked at the bill in detail seems to pretty much hate it. It would have been better split up into multiple, smaller pieces of law that each tackled a specific purpose. In practice, though, that would not have helped the aims of the UK’s intelligence and security agencies, who are hoping for the halo effect of “protecting children” to allow them further sweeping online powers.

Of most concern are provisions in the bill that civil society groups and big tech companies alike say will undermine encryption, and thus undermine both privacy and security. Ministers and departmental spokespeople routinely say this claim is inaccurate, but no-one has ever to date created a back door in internet security that only one party can use.

The government is essentially ordering big tech to invent this new thing – which is much the same as passing legislation requiring McDonald’s to invent levitation. You can try to blame them when they fail, but you’re going to end up looking silly too.

The latest development in the years-long saga was a joint statement from multiple messaging apps – including Meta’s WhatsApp and Signal – saying that if this legislation passes, they will withdraw their services from the UK rather than comply.

Big tech has cried wolf on this front before – but I’ve spoken to people at Signal, as well as people at multiple levels of seniority at Meta, and the strong message I am hearing (which I believe) is that this is no bluff.

The lack of viable technology to actually accomplish what the government wants, coupled with the need to set limits to other countries, and the lack of revenue generated by WhatsApp (for Meta) means that those in the company are sincere in believing it would be better to cut the UK off than to comply with the Online Safety Bill.

That confrontation is not a good one for the UK government. The UK economy benefits from being seen as a reliable place to do business, and London is home to thousands of big tech employees. After the relentless instability of Brexit, the last thing that employers want is a new online cut-off – an Internexit, if you will..

And all of that is before the government is plagued with relentless messages from people annoyed to be cut off from their messaging services. MPs should be careful what they wish for, as they’re set to get it – this bill is likely to pass. They may find themselves wishing it hadn’t.

Gamers gonna game

The US military loves recruiting gamers, and loves working with the games industry as they make shoot ‘em ups – doing so with different tactics over the last two decades. These efforts went so far as creating a video game, America’s Army, as an explicit recruitment tool. It was in operation for 20 years, before it was shuttered last year.

Gaming culture and military culture are, then, not two separate phenomena, or two communities that overlap only coincidentally. Discord is second nature to a sizeable chunk of the US military, even more so than would already be expected for a group predominantly made up of young men.

All of which is to say that the fact that alleged military secrets leaker Jack Teixeira decided to share not with the world but a small gaming community should not have come as the slightest of shocks to US intelligence – and it certainly shouldn’t have taken so long for them to be detected.

This isn’t a tech platforms issue: as others have noted, calling these the “Discord leaks” is to confuse the medium with the message. It is as much of a category error as calling the Edward Snowden leaks of ten years ago “the USB stick leaks”. Yes, it’s the medium that was involved, but is it really where the focus lies?

The reality of this leak seems to be that it wasn’t motivated by ideology or money – it was motivated by Internet Points, the catch-all term for online currency and credo among different sub-communities. And that is a matter of culture far more than it is of platform – what you do to chase Internet Points on Reddit is different from what you do on 4chan, or Discord, or Twitter, but we’re all doing the same thing.

Those advocating for platform regulation might want to remember that: the common factor across all those platforms is not UX design, or unlimited scroll, or anonymity, or any one of a dozen other issues. It’s who is using them and how we are wired as a species.

The US intelligence community should reflect on the fact its threat model seems to have missed out on Internet Points entirely – and unaccountably, given part of their job is to understand the internet. They may also wish to assess whether three million people really ought to be going around with Top Secret clearance and the ability to fish outside their domain.

Multi-polar tech is coming, and the US has no chill about it

We are creeping up on ten years’ since the Edward Snowden NSA revelations in the Guardian and Washington Post. One of the key revelations from the vantage point of a decade later is that it showed how willing the US was to exploit its first-mover advantage in technology.

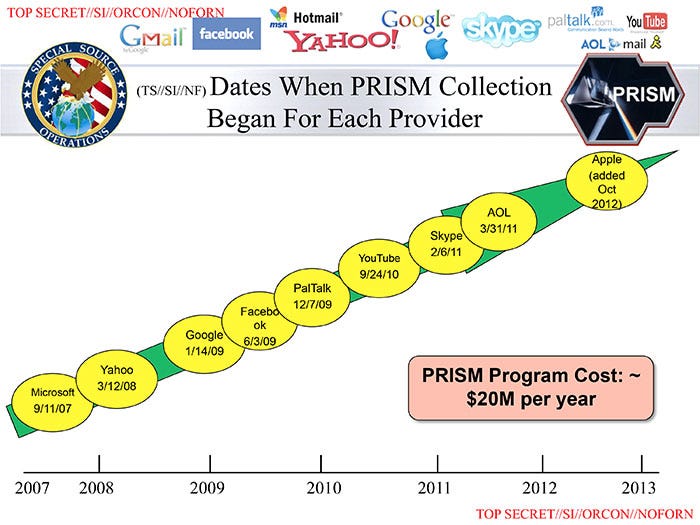

The PRISM slides were as telling for the vibes they gave off as for the details of the program itself. Tech company logos were lined up alongside those of the National Security Agency, suggesting they were almost just outcroppings or subdivisions of the USA’s security state.

Telecoms companies and internet service providers, meanwhile, were coopted to collect bulk data on both their domestic and overseas users, while further revelations showed that even with all of that collection at their disposal, the US was willing to hack into US tech giants (for whom it provided security advice) to improve its intelligence access.

This was then used to spy on enemies, adversaries and allies alike – prompting outrage both faux and genuine across the world, and leading to significant changes in the operation of the internet. Given most tech giants were American, and America had shown it would exploit that to a huge extent, the internet needed to be built on security and privacy instead of on trust.

The new era of the internet does just that: https is default for browsing, and end-to-end is expected for messaging. In a world where you don’t control every hop of the infrastructure, strong encryption is the only way forward.

With its often overblown reaction to non-US tech companies like TikTok, the USA is flailing. The internet is a global network, and countries across the world let US tech companies oversee huge amounts of their digital architecture. If the US can’t allow other countries to sit at the table too, what little trust remains will already start to pour away.

That doesn’t mean the US needs to start opening up all of its networks and making itself vulnerable – but it does mean that the US might want to more enthusiastically work to beef up the security of protocols and standards online.

The US-centric internet has been ascendant for quite some time, but it has been in decline since before the Snowden leaks. It will not last forever, and the multipolar internet is coming. It is bizarre that the USA seems to have no response to any of that.

In the news

· Twitter’s user numbers have fallen for the third month in a row, reports Vox, and this time it’s by 7.7%. Given the platform is still at war with its power users, has shed three quarters of staff, and seems to have no onboarding for new users, this could be the start of a death spiral.

· Did this charity use an AI-generated image in its social media publicity? And is that as bad as hypothetical food companies using AI-generated product shots (which is a total non-starter)?

· Elizabeth Holmes is going to prison at the end of this month.

· This apparent gaslighting from Snapchat’s AI assistant is…alarming.

· Anyone remember the metaverse? We lost interest in that even faster than NFTs, huh. I suspect the former will bounce back more than the latter, though.

And finally…ticked off

We’ve been doing the Twitter verification hokey-cokey this week – in, out, and shaken all about. I wrote about the anticlimactic moment for the New Statesman, but since then we’ve had further developments that change the product on offer yet again.

This is the rough history of Twitter verification, in five steps:

A verified ‘blue tick’ (the tick is actually white) means Twitter staff have deemed this account to be notable – a journalist, celebrity, public figure or similar – and have confirmed their identity

A verified ‘blue tick’ (the tick is actually white) means Twitter staff have deemed this account to be notable – a journalist, celebrity, public figure or similar – and have confirmed their identity, or that someone has paid $8 a month to get a tick, and you can tell which is the case by checking a tooltip

A verified ‘blue tick’ (the tick is actually white) means Twitter staff have deemed this account to be notable – a journalist, celebrity, public figure or similar – and have confirmed their identity, or that someone has paid $8 a month to get a tick, and you can not tell which is the case by checking a tooltip

A verified ‘blue tick’ (the tick is actually white) means that someone has paid $8 a month to get a tick and has a confirmed phone number linked to their account, or is one of three celebrities that Elon Musk has given a tick for free

A verified ‘blue tick’ (the tick is actually white) means that someone has paid $8 a month to get a tick and has a confirmed phone number linked to their account, or is one of three celebrities that Elon Musk has given a tick, a further handful Elon Musk has given a tick as a ‘punishment’, or reflects that this is an account with more than one million followers

The first definition of a tick lasted for 14 years. The other four have all been true at different points in the last month. The whole thing will make an amazing case study in how to destroy value, and how difficult it is to rebuild: celebrities and journalist were secretly proud of their ticks, but the social rules have changed. It’s much cooler now not to have one.

The whole point of exclusive clubs is that they’re exclusive: the second anyone can get in, the original crowd leaves. That’s as objectionable as it sounds, but it’s true.

By re-ticking everyone with over a million followers, Musk is trying to make the ticks cool again – you get boosted like these huge accounts do. But the problem is that when a tick either means “paid for it” or “has a million followers and didn’t”, it is not exactly hard to see who is in which group – 300 followers and a blue tick? You bought it.

The danger will come when Elon realises this, as the logical next course of action at that point is to hide follower counts – which could be justified on spurious but sanctimonious grounds of ‘equality’ or egalitarianism.

It would destroy one of the last remaining ways of verifying an account is who they say they are, and spotting new accounts and hoaxers – but it would briefly fix the latest iteration of the blue tick problem.

It’s the most damaging but logical next thing I can think of for Elon to do, so I can only assume it will be policy by the time you read this.

Until next week,

James

(Techtris was written by James Ball and edited by Jasper Jackson)